Young couple strives to keep Indigenous wedding traditions alive

By: Alexander Kim and Peggy Lam

By: Alexander Kim and Peggy Lam

This May, two young members of the Nlaka’pamux First Nations are hosting a rare gathering.

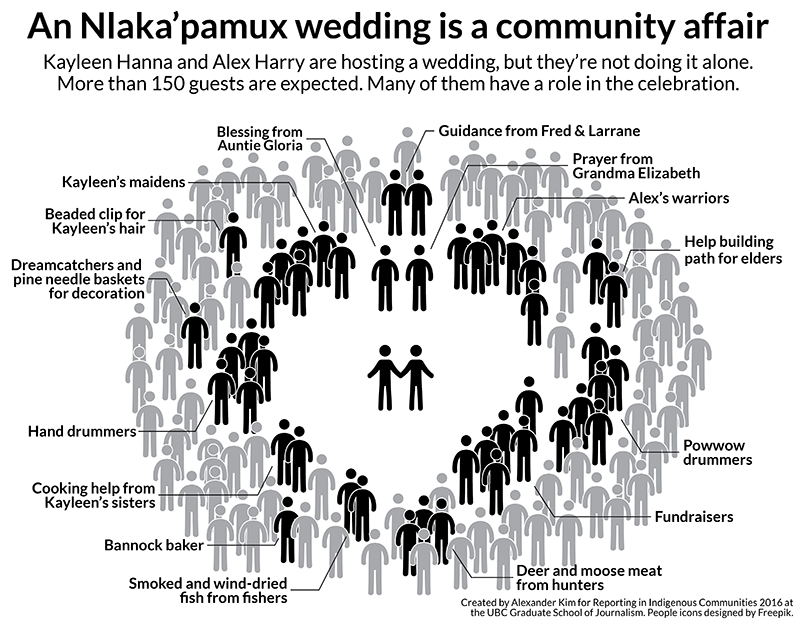

Alex Harry and Kayleen Hanna, both 25, are inviting more than 150 family members and friends to the edge of a cliff at Nicomen Falls, a four-hour drive from Vancouver into Interior B.C., to witness a traditional wedding.

In many Indigenous communities, wedding traditions were lost due to colonization and the Indian residential school system. But in recent years, some marriage ceremonies have been making a comeback.

Alex and Kayleen are members of the Nicomen and Lytton Indian bands near Lytton, B.C. They say they want a wedding that reflects their heritage and values.

“If you do it the traditional way, your ancestors are there and you’re making them happy,” Kayleen says.

Their wedding will be at the top of a waterfall on the Nicomen Indian reserve where Alex grew up. Community elders will conduct the ceremony in the Thompson language, drummers will perform Nlaka’pamux songs and there will be a potluck with traditional foods.

It wasn’t easy for Alex and Kayleen to plan the wedding. There aren’t many people who know how to throw an Nlaka’pamux wedding.

They turned to 73-year-old elder Fred Henry for help. Henry and his wife, Larrane Leech, held a traditional wedding in Lytton in 2010.

As a survivor of the St. George’s Residential School, Henry grew up disconnected from Nlaka’pamux culture. But when he and Leech decided to get married, they wanted to have a ceremony that blended traditions from both Nlaka’pamux and Snuneymuxw First Nation, where Leech is from.

Henry asked his elders about Nlaka’pamux wedding traditions, but it didn’t get him far. Those ceremonies fell out of practice a long time ago and were forgotten.

That didn’t stop Henry. He made his best guess.

“I done it the way I thought it would’ve been,” he says.

He started with his regalia. No one from Nlaka’pamux knew how to make it, but Henry had an old photograph of his great-grandfather wearing buckskin regalia. He brought the photo to an artist at another First Nation and asked her to fashion something as close as possible.

Since the photo was black and white, they had to guess what colours to use. They decided on red, black, yellow and white — to represent the four directions — with green and blue — to represent the universe.

On the day of the wedding, more than 650 people showed up.

“I had all my warriors and Larrane had all her maidens,” Henry says. “As we were coming in, everybody was drumming. They were drumming us in.”

Many of their guests came from other First Nations. Henry says none of them had ever seen a traditional wedding before. There was a line of people outside waiting to get in.

“Larrane and I were proud of that,” Henry says. “I thought we done a pretty good job.”

Grand Chief Stewart Phillip of the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs believes marriages are becoming more common among Indigenous couples. He says it reflects a trend in communities healing from the historical traumas of residential schools.

“I think anything we can do to create that sense of stability in our communities, such as marriages, is helping,” Phillip says.

Phillip is a marriage commissioner and has officiated more than 70 weddings, mostly for Indigenous couples.

The weddings he sees often blend Indigenous and Western traditions. Other Indigenous couples are reviving traditions that haven’t happened in a long time.

When Noelle and Ray Natraoro got married in 2008, they did it with a Squamish custom that hadn’t been performed in more than a century. They spent an entire year preparing for it.

“My wife made necklaces and earrings, bracelets out of abalone, dentalium shells. I got together boxes, copper bracelets, some masks, prints, blankets,” Ray says.

Their wedding ceremony involved a 12-hour voyage by canoe, a procession from the beach to the longhouse, mask dancing and a blanket ceremony. The couple gifted each of their 500 guests with a precious hand-woven blanket.

The Natraoros say they revived the tradition because they wanted to represent where they come from.

“It was in my dreams and my upbringing to honour my ancestors to let them know that this is who we are,” Ray says.

Alex and Kayleen also want to represent their heritage by following Fred Henry’s example.

At their wedding, hand drummers will play and sing as the couple walks in. The walkway will be strung with boughs of cedar, a sacred tree to the Nlaka’pamux.

Alex’s aunt Gloria Phillips will give a blessing in the Thompson language. His 98-year-old grandmother Elizabeth Lytton will say a prayer.

Kayleen will wear a beaded hairclip with a rose on it to remember her grandmother, Beatrice Rose, who passed away in 2000. Their corsages will be crafted with native plants such as cedar, thyme, juniper and Douglas fir.

Alex and Kayleen say the whole community is involved in the event.

Guests will bring their signature Nlaka’pamux dishes to the potluck wedding. Wind-dried fish, deer steaks and bannock are some of the items on the menu.

Alex had his friends come to Nicomen Falls to help build a separate pathway for the elders to walk up the cliff.

“Every time I went up there, I was never alone because they all came in to chip in,” he says.

Fred Henry says seeing Alex and Kayleen carrying on wedding traditions makes him hopeful.

“Never thought that would happen, but it did,” he says. “I’m going, ‘Right on! Somebody was listening.’”

Kayleen hopes to pass the traditions along to her future children.

“We’ll be able to tell them we did it our way, because we are our own people,” she says.

The wedding is set for early May, on Nicomen territory.

Peggy Lam is a multimedia journalist based in Vancouver. Follow her on Twitter @peggylam_

Alexander Kim is a journalist and radio producer based in Vancouver. He tweets @alexanderbkim