Group aims to break silence about sex for Tsleil-Waututh youth

By: Megan Devlin and Rohit Joseph

By: Megan Devlin and Rohit Joseph

Lexus George never had “the talk” with his parents.

“I’ve never really asked them questions about ‘the birds and the bees,’” he says.

The 19-year-old thinks his parents could have been uncomfortable because of the history of residential schooling in his family. He doesn’t pry.

As a result, the young member of the Tsleil-Waututh Nation got his first introduction to sex in high school, when a teacher entered the room wearing condom on her head to demonstrate their durability. Now, he says he doesn’t want to stay silent when he has kids of his own.

“I’ll try to tell them everything I know, how to stay safe and protect themselves. I want to make it fun too… so maybe I’ll try putting the condom on my head,” he chuckles.

But silence between parents and kids around sex is common at Tsleil-Waututh — a tight-knit community of just over 500 people in North Vancouver. Many suggest the hush stems from grandparents sexually abused at residential schools.

Hundreds of Tsleil-Waututh and Squamish Nation children were boarded at St. Paul’s Indian Residential School until it closed in 1958.

“Everybody in my parents’ generation from Tsleil-Waututh went to residential school,” says Luke Thomas, 50, Tsleil-Waututh’s Family Programs Coordinator.

Thomas says his parents came out devoutly Catholic. When he was growing up, sex was only talked about in terms of sin.

“If you had sex before you got married, you were going to hell. If you had sex for anything other than conceiving a baby, even after you were married, it was still a sin,” he says.

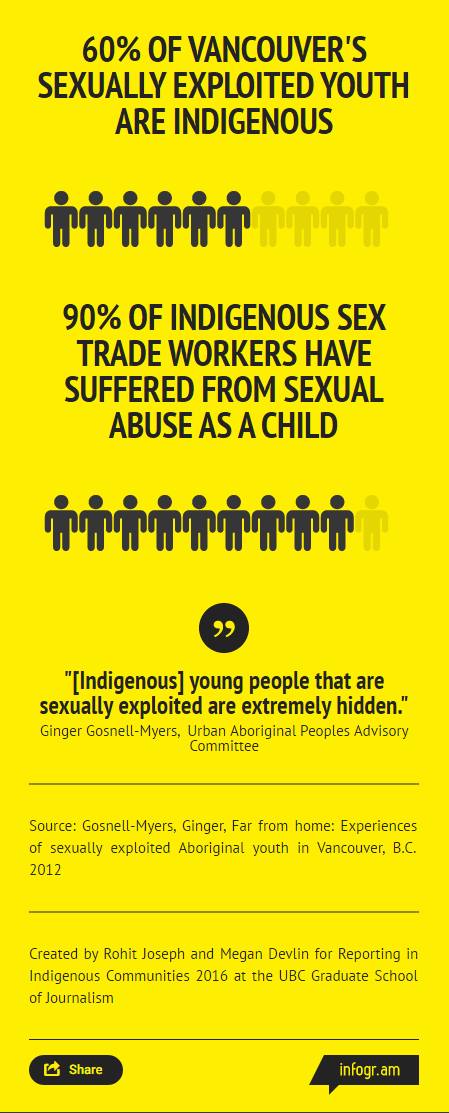

Residential schools did more than cast a shadow on consensual sex. Sexual abuse at the hands of priests and nuns inflicted intergenerational trauma. Indigenous people are still disproportionately affected by sexual exploitation — 60 per cent of sexually exploited youth in Vancouver are Indigenous, and sexual violence is a recurring theme in Canada’s missing and murdered indigenous women cases.

But, one woman at Tsleil-Waututh is determined to change that.

Cheyenne Hood calls herself an outlier at Tsleil-Waututh. The 41-year-old mother of three says she’s atypical in the community because she made a point to talk to her kids about sex.

“Knowing what I know about statistics about teen pregnancy, I felt like I didn’t want my kids to go through trial and error,” she says. “I didn’t need to be a 34-year-old grandmother.”

Hood is the Nation’s housing manager, and found she has a knack for writing proposals. This year, she helped secure funding for a new program called Passing the Feather that trains youth workers to talk to youth about sexual exploitation.

“I think that the vulnerability level is extremely high in First Nations communities for exploitation,” Hood says. “The layers are so deep and there’s so much to dissect.”

Passing the Feather’s name comes from the idea of a sharing circle, says iris yong-pearson (who prefers not to capitalize her name), a youth worker with Peernet BC who serves as the group’s facilitator.

“In many Indigenous cultures, they use the talking stick or passing the feather to give each other space to share our stories,” she says. “This project is about sharing our stories and holding space so that we’re able to talk about a really tough topic.”

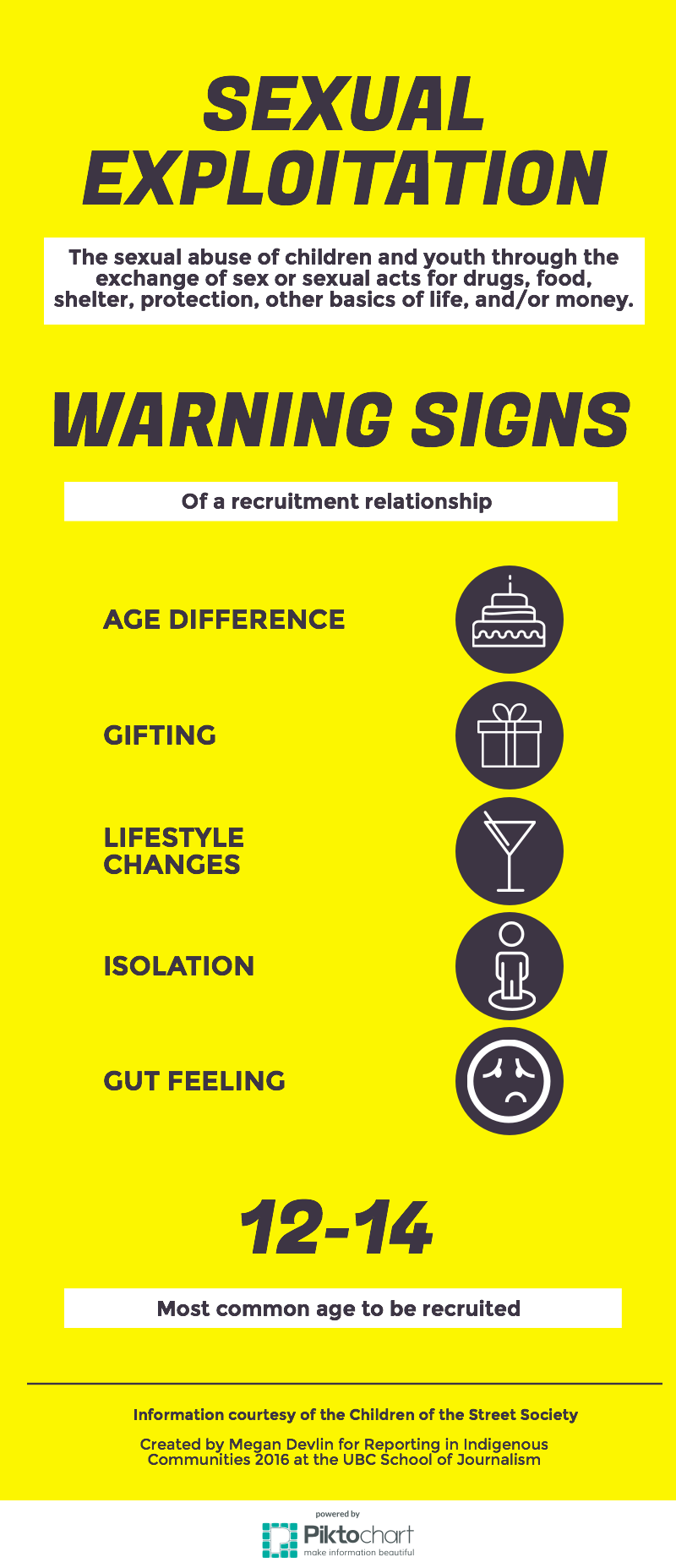

But Passing the Feather is more than just talk. It’s a series of workshops that gives youth the tools to spot predatory behaviour and offer guidance to peers about sexual exploitation. The group meets on Wednesdays, alternating between the Tsleil-Waututh band school and Parkgate Community Centre.

yong-pearson gets kids in the door by selling them on the concrete facilitation skills they’ll learn for future careers as youth workers. She motivates them to open up about sexuality by framing the conversation with a purpose — helping potential victims of sexual exploitation.

She uses conversation cue cards to train them to open up conversation about tough topics. Listening exercises help them handle disclosures from peers. Guest presentations give youth background knowledge of the risk of sexual exploitation in Vancouver.

The group is building toward a multimedia workshop about sexual exploitation for the Tsleil-Waututh community. They’re hoping to have it ready by June.

Hood isn’t sure youth heading into the workshops will understand what “sexual exploitation” even means. But by the time they’re done, she hopes, they’ll recognize what she calls “a long colonial history of sexual exploitation.”

“Being taught from generation to generation not to talk about sexual abuse and to be ashamed of it… that’s where some of the [hesitation] stems from,” she says.

She doesn’t expect grandiose changes immediately—but hopes to spur a gradual cultural shift.

“For the first time kids in this community are going to have the opportunity to say the word ‘sex,’” she says. “Being realistic, my greatest hope is just to initiate the beginning of the conversation.”

Megan Devlin is a Canadian multimedia journalist. You can find her on Twitter @MegDevlinn

Rohit Joseph is a journalist with a penchant for audio storytelling. You can follow him on Twitter @RoTomJo