14 Apr Unshaken faith: Keeping the Shaker Church alive

By Wawmeesh G. Hamilton and Gen Cruz

Eugene Harry stomps his feet and rings two black-handled silver bells, as he sings with a deep howl in the Hul’q’umi’num’ language to a congregation gathered in a white-steepled church in West Vancouver.

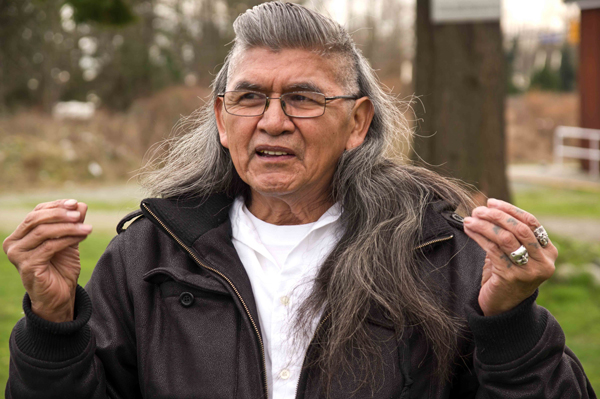

For over thirty years, the bespectacled silver-haired Eugene has ministered the Indian Shaker Church, a unique meld of aboriginal and Christian beliefs.

It’s a faith outsiders rarely see, and it looked as if the Shaker Church might disappear altogether at the Squamish Nation. During the past decade, the congregation has shrunk to less than nine people, said senior church member Al Harry (no relation).

Shaker members circle three children with candles and bells under a cross suspended from the church ceiling as part of a baptism ceremony. (Photo: Wawmeesh G. Hamilton)

“For the longest time (Eugene) was the only one coming to church,” Al, 63, said. “He came and he prayed alone.”

Now, Eugene, 65, has made it his mission to pass the Shaker faith on to a new generation, hoping faith helps them like it helped him.

“I was an alcoholic and even homeless and walking a dark road before I became a Shaker,” the father of six said. “If someone told me when I was young that I’d be a Shaker minister one day, I’d have said ‘When hell freezes over.”

Church shakes up history

According to the academic paper Shaking Up Christianity, the Indian Shaker Church was founded in 1881 in the Pacific Northwest, by a Coast Salish man who is said to have died — then returned to life to start a new religion.

Witnesses said John Slocum’s legs were shaking when he awoke from the dead, hence the term ‘shaker’.

The first Shaker Church at Squamish Nation was built in the mid 1900s, by the late Isaac Jacobs. The nation now has two churches, located in Squamish and West Vancouver.

Eugene conducts services every other Saturday evening. Outside, an area beside the church is used to burn food for the dead. Inside, three crosses stand at the altar, signifying Christ’s crucifixion. Bells and candles are used during services.

“Bells call the Creator, they’re like drums. And candle light points to the direction of the Lord,” Al said.

Men and women sit on separate sides of the church, but gather in the middle, under a large cross suspended from the ceiling.

Some church members also practice Cion (pronounced see-own), the Squamish people’s traditional spirituality, in the longhouse 50 metres away from the Shaker Church. The two practices co-exist in Squamish.

“We respect them as much as they respect us,” Shaker elder Jane Wilson-Charlie said. “It’s like what Eugene would say, that we’re all a family. It’s like a brother and sister.”

Christianity and aboriginal spirituality didn’t always exist harmoniously. After colonization, churches considered aboriginal practices as pagan and tried to eliminate them. The church-run Indian residential schools were one such method.

Darkness before light

Eugene, who was born on the Cowichan Reserve on Vancouver Island, was sent to residential school but ran away after enduring physical abuse.

He lived with his grandparents and remembers hearing shakes – the name for Shaker services – held nearby, but never took part. The death of his grandparents ushered in a long period of alcoholism and jail time for Eugene.

“I hated God as soon as my grandparents died,” he said. “I had so much hate for

God, that (He’d) taken away all my loved ones, I had no use.”

Shaker church minister Eugene Harry talks about how his congregation numbers lowered at the same time as the residential school issue came to prominence. (Photo: Wawmeesh G. Hamilton)

But things changed when he met his wife Wendy Louis, a Squamish First Nation member and a Shaker.

Eugene was attending a Shaker service with his wife, and declined a request to bless food. An elder told him she remembered his late grandfather blessing meals at Shaker functions. “She said, ‘If you’re a true grandson of your grandfather, you must have the same words.’”

Eugene prayed, remembering his grandfather’s prayers. The moment was pivotal. On Labour Day 1984, he quit drinking and began regularly attending Shaker services.

From student to teacher

Eugene recalls Shaker elders who influenced him to become a minister in 1987: Walker Stogan, Josephine Grant and his in-laws.

“I had aunties and uncles who coached me, showed me, shared with me,” he said. “I had great teachers.”

But over the past decade, Shaker Church congregations have declined from 20-40 to fewer than nine people. Eugene blames alcoholism – the Shakers disallow alcohol – and the impact of residential schools.

Revelations of abuse against students in residential schools rose in public prominence after several court cases over 20 years. The timeline coincides with the drop in congregation.

“Their parents and my parents went to residential schools,” he said. “They adopted the thing that they hate God too.”

Eugene even sang alone in an empty church some months. He prayed for people to come back. When he despaired, he prayed to the man who raised him.

“Being alone brought me closer to my late grandfather because I said ‘Help me continue on your words; help me share the songs – help me walk through this,’” he said.

Eugene’s prayers weren’t in vain. The church is no longer empty. People are trickling back.

“New people come because they want help with personal issues,” Al said. “They’re under the influence (of alcohol). But we won’t turn them away. I was there once.”

Praying for a miracle

A generational shift is starting again in the church. Young members now look to Eugene and Al for wisdom.

“We didn’t think of ourselves as elders but others did,” Al said. “I’d talk to young people in church and find myself saying the same things my elders said to me.”

At a recent Sunday service, three Squamish Nation children were baptized.

Eugene and the congregation sang a hymn. The members held lit candles and circled the children three times, stopping at each child to say a blessing. Eugene then blessed them with a candle and holy water.

The baptism is replenishing the small congregation, which, to aging church elders means hope for the future.

“They say a miracle happened everyday through this faith and so we keep praying that this keeps going on,” Al said. “How long did we hear that miracles will happen and that we’ll witness more of them? It’s something I’d love to see.”

Stories

Education credits remain elusive to many residential school survivors

|