By Pratyush Dayal and Joshua Azizi

Carol Gabriel has lived on McMillan Island all her life and doesn’t plan to ever leave. But with the climate warming, water levels are expected to rise and that means an increased risk of flooding.

“Climate change is really affecting us on this island,” said Gabriel. “But nobody wants to leave. This is their home.”

The Kwantlen First Nation is doing what it can to prepare. On McMillan Island, where 100 people live, risk assessments happen constantly. Climate change projections have been reviewed and the First Nation is stepping up emergency planning in case of evacuation.

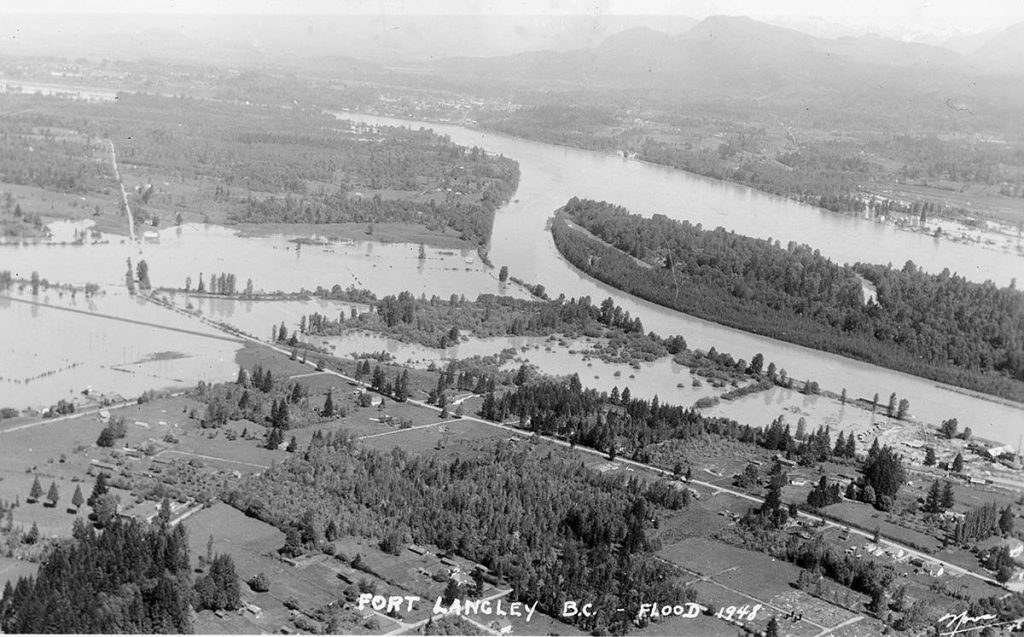

Kwantlen First Nation has seen many floods over the years but the last catastrophic flood was in 1948. The Fraser River had swallowed much of the valley, forcing 16,000 people to flee and destroying roughly 2,000 homes.

Gabriel wasn’t yet born when the 1948 flood hit. But she remembers the 2012 flooding season when the Fraser River inundated the island, flooding the boardroom and basement of the band office.

“I’ve seen a sturgeon swimming that way, and I go, ‘oh my god, there’s a big sturgeon just swimming,’ you know, past the building here.”

The clean-up effort was extensive.

“We had to sanitize the whole thing because water brings down sewage in…. We all had to get in our hazmat suits and get our gloves on and start cleaning and scrubbing everything.”

She and others on the island know that climate change predictions have only increased their vulnerability.

Kwantlen in a ‘double whammy’ with flood risk

Research from groups like the Fraser Basin Council show that major floods in the region are expected to increase in frequency and magnitude due to climate change.

Gabriel is witnessing changes to the local climate firsthand.

“We’re noticing right now that the flood is coming sooner,” she said.

The “flood” Gabriel is referring to is the annual spring freshet — the time of year when the water levels rise due to heavy rains and melting snowpacks — is coming earlier.

“Because of climate change, everything’s changing, like everything’s early,” she said.

Regional climate models focus on two areas when it comes to assessing flood risks: coastal flooding from sea level rise, and river flooding due to larger peak flows on the Fraser River.

Future flood model maps, completed by the Fraser Basin Council, detail what major floods over the next century might look like for McMillan Island residents.

The models focus on different scenarios in the years 2050 and 2100, and show that major flood events, coupled with sea level rise, would completely inundate the island, requiring residents to be evacuated.

Stó:lō Tribal Chief Tyrone McNeil said this leaves Kwantlen in a “double whammy, because they’re in a tidal zone plus the river rise.”

Kwantlen isn’t the only Stó:lō reserve community facing both threats, several Stó:lō First Nations have been working collectively on flood mitigation projects with the Fraser Basin Council.

Still, Kwantlen is also working on its own specific planning.

The First Nation knows what it’s up against. McMillan Island is very much a part of the Nation’s traditional territory, but because of the Indian Act and the reserve system, there are limited places for residents to go to.

“The land was designated by the federal government. The First Nations did not have any real say in what the land was going to be,” said Elaine Kenny, project manager for Kwantlen First Nation.

‘We need to do the best we can’

There are challenges and limits to what can be mitigated on the low-lying island. For example, building dykes and flood walls isn’t an option because of cost, said Kenny.

Still, the Nation is doing what it can.

Included in those efforts is knowing when and where to start sandbagging when the flood risk spikes. There are also longer term efforts like changing building codes to raise the minimum elevations for new builds.

“We need to do the best we can with the land that has been given to the members,” said Kenny.

Kwantlen is also looking to raise the elevation of critical infrastructure and roads — including the only road off-island, which is crucial in the event of an evacuation.

“Our biggest priority is creating an emergency response plan that will assist with evacuation when necessary, and all the protocols that we would need,” she said.

Over the years, Gabriel has found her own ways of keeping an eye out for the flood risk. The Bedford Channel passes right in front of her house, which she built 26 years ago.

“When it’s freshet, I have some viewpoints. One behind my place, if there’s a big pond,” she said.

“And there’s a farm field and a golf course off Glover Road. And if those two fields have totally flooded, that’s when I really know that it’s going to flood.”

She knows how to watch for trouble.

“I’ve lived here all my life and I say, ‘If you see me leaving, then you go,’ but I’m not gonna leave until I know it’s really crucial.”

Pratyush Dayal is a multimedia journalist and author, raised in India, presently based in Vancouver. You can follow him on Twitter @Pratyush_Dayal_

Joshua Azizi is a journalist based in Vancouver. He’s interested in reporting on municipal affairs, social justice and popular culture. You can follow him on Twitter at @joshuaazizi