By Alejandrina Alvarez Debrot and Riley Tjosvold

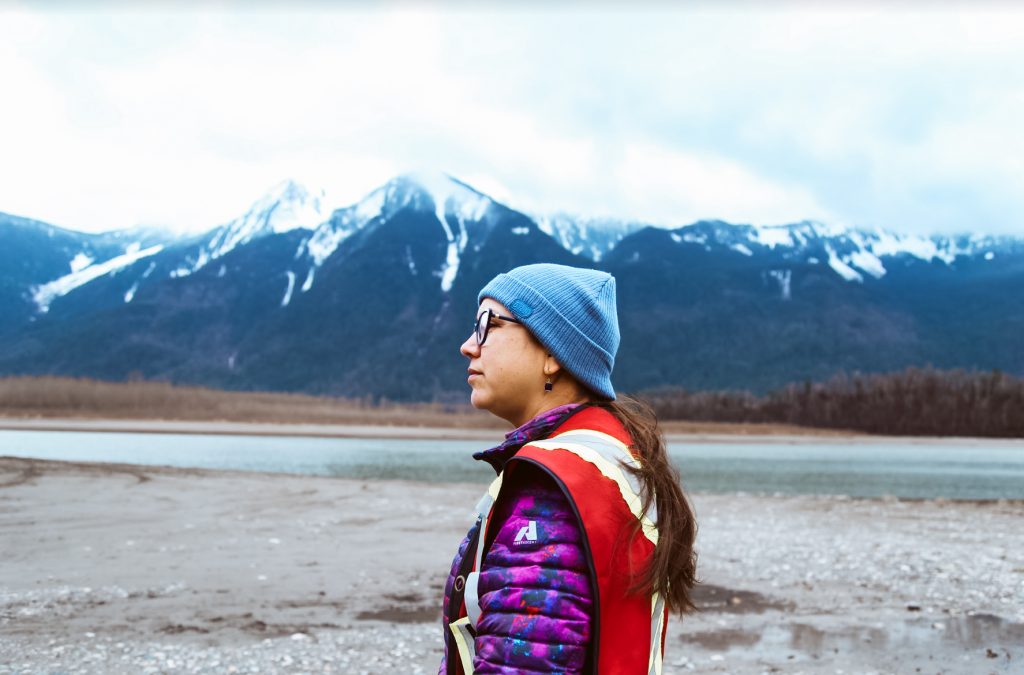

Carrielynn Victor is intimately familiar with the banks of the Fraser River at the Cheam First Nation Fishing Village, located just over 100 kilometres east of Vancouver. She led a team of workers who planted trees there, removed invasive plant species, dug pools, placed logs, and hauled sediment from the bottom of a river side-channel.

The team’s goal: to restore spawning habitat for chum and coho salmon.

Their work is part of Cheam First Nation’s effort to improve the survival odds for salmon in an era when their existence is increasingly threatened by climate change and additional, cumulative impacts to their habitats.

Victor said for many people in Cheam, who identify as Stó:lō, working to help the salmon is more than just a job, it’s a responsibility.

“Salmon are very significant,” she said. “We relate to salmon as a type of people.”

Stó:lō people have fished the Fraser River for thousands of years. In recent decades, many salmon populations of key cultural significance have been vanishing from river systems in British Columbia.

A 2019 report from Fisheries and Oceans Canada detailed that climate change is a major culprit in that decline and predicts if climate patterns stay on their current trajectory, many salmon returns will continue to drop.

But Victor and her team at Ayelstexw — a Halq’eméylem word that translates to “leave it in good health” — are determined to help salmon that travel the Fraser River find their way to cooler waters.

‘We’ll cool it down just a couple of degrees’

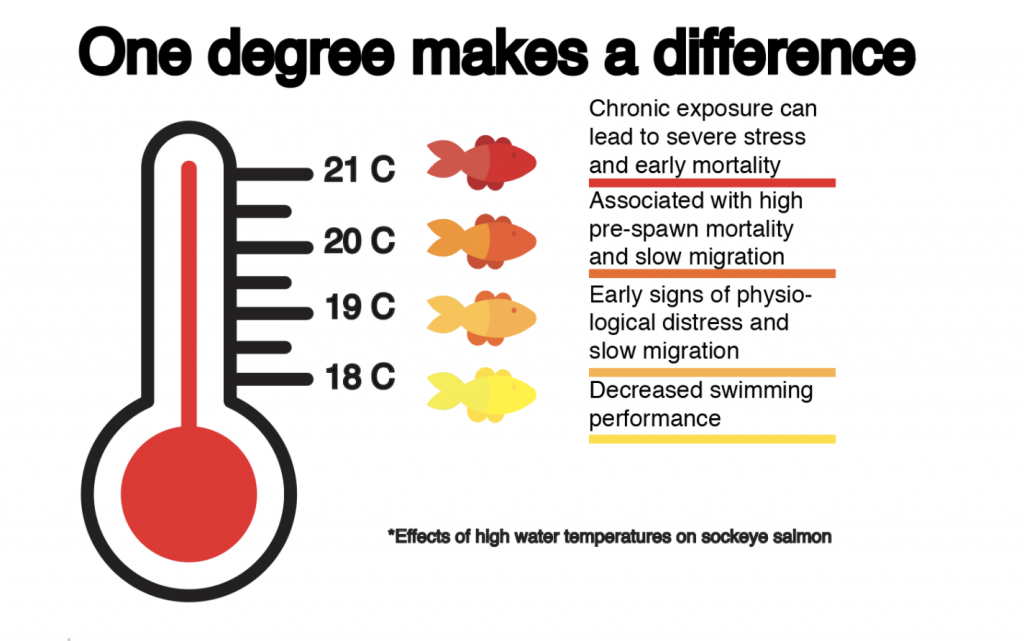

Increasingly high water temperatures are just one of many challenges salmon populations are facing.

It’s also something localized habitat restoration projects, like the one Victor’s team is working on, can mitigate. Part of their current project involves re-introducing riparian plans on the river bank to provide more shade.

“We’ll cool it down just a couple of degrees to create cool water pools and then keep that groundwater, that’s always cold, upwelling into the side channels of the river.”

Victor has seen what happens to salmon when water temperatures get too high.

“A number of years ago when we were harvesting fish their skin could literally just rub off. The water was so warm that you could grab a salmon and it was just mush,” she said.

Researchers investigating the Fraser River have measured the water getting warmer and staying warmer for longer over the past several decades.

Temperatures of 18 to 20 degrees Celsius exhaust some salmon, like sockeye, as they travel upstream to spawning grounds. The stress can increase their pre-spawn mortality rate and harm their eggs.

For coho, a fish that spends more time rearing in freshwater than some other species of salmon, rising water temperatures are particularly detrimental.

Ernie Victor, Carrielynn’s cousin and fisheries manager for Sto:lo Research and Resource Management, helped design parts of the restoration, which he calls “a gesture of compassion.”

Victor’s team applied to do habitat restoration when they discovered coho in the channel at the Cheam fishing village site.

“You destroy something and you want to do something to make it better,” he said.

In his own lifetime he’s seen impacts of the declining salmon population in the community.

“I remember my dad and my grandpa knew every farmer and local resident, and they were sharing and bartering for chicken and eggs, and everyone had a taste of salmon,” he said.

“So that interconnectedness with the non-Native community is not there anymore.”

Victor is well aware of the cumulative impacts that salmon are up against — forest fires, dry weather, warmer oceans, overfishing and construction activities in and around salmon habitats.

“You can’t just say it’s climate change… it’s all these factors when it comes to salmon,” he said.

‘Every little bit helps’

Conservation biologist Misty MacDuffee, who specializes in salmon, applauds restoration projects, but said they will be a “Band-Aid solution” unless they “are accompanied by a change in our governance structure and how we prioritize the health of our ecosystems.”

MacDuffee says projects that damage salmon habitat — like clear-cutting forests, hardening riverbanks, and building marine container terminals — are happening more frequently and at a larger scale than habitat restorations.

“You look at these decisions, and you look at climate change, and that’s when you think ‘these fish haven’t got a chance,'” she said.

Researchers also caution that climate change could create environmental conditions so severe that habitat restorations may be fruitless.

All of this knowledge has left Carrielynn Victor feeling powerless at times.

But she’s determined to do more restoration work along the river, while leaders from Cheam have been meeting with nearby communities to see if they can collaborate to create more spawning habitat.

Knowing how climate change is impacting the fish encourages her to move forward on more habitat projects.

“Every little bit helps,” she said.

Coho will begin returning in late spring, which means Victor and her team will soon be able to get a sense of whether their project is a success.

Regardless of what they find out Victor said, “we’re just gonna keep pushing.”

Alejandrina Alvarez Debrot is a Venezuelan-Canadian journalist who loves writing about social justice issues. She a political science degree from the University of Toronto. Follow her on Twitter: @aledebrot

Riley Tjosvold is from Alberta. He likes writing about art, culture, politics and the occult. Follow him on twitter @rileytjosvold