By Emma Loy and Yusheng Cai

A stream of people winds its way through the gravel parking lot in front of St. Paul’s church on Mission reserve in North Vancouver. Cardboard boxes are unloaded from the deck of a Squamish Nation truck. Laughter mingles with birdsong as band members wait patiently to get two cases of sockeye salmon – a prized food of the Squamish people.

Every year, the Squamish Nation distributes fresh sockeye for free to ensure the community has traditional food.

But this year is different. For the first time in Squamish history, the Nation is distributing canned salmon bearing the Squamish Nation’s crest—the Nation’s solution to keeping tradition alive when both fishermen and fish are scarce.

Disrupted distribution

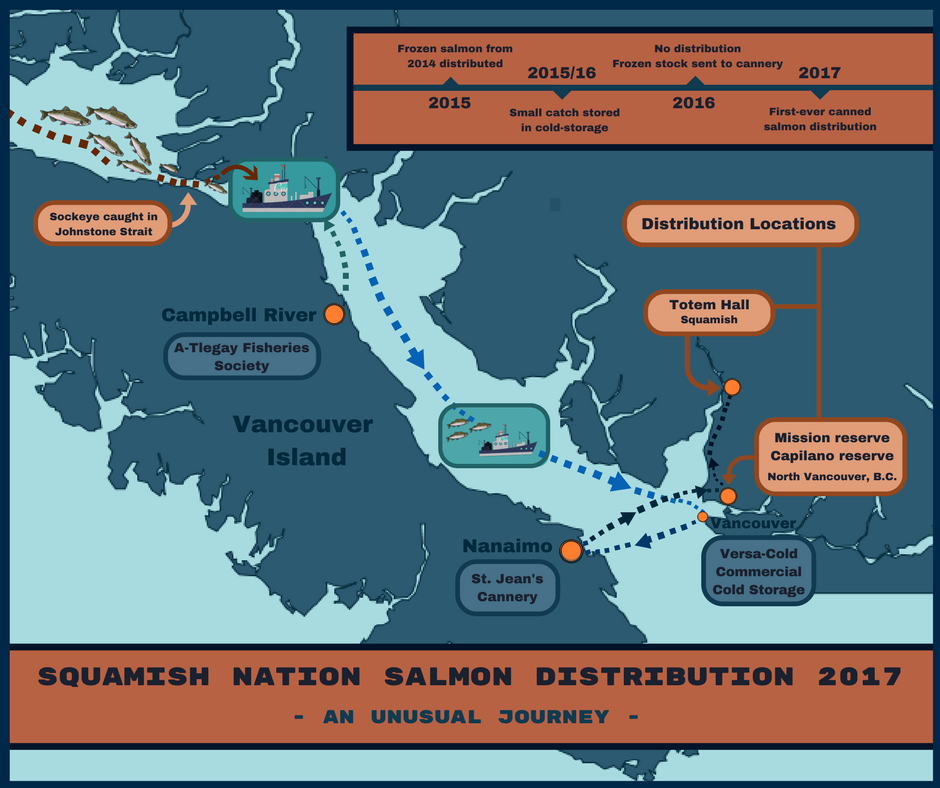

Fresh salmon is usually given out in August, but in 2015, sockeye returns were poor, so the nation distributed frozen surplus salmon and put some sockeye in to cold storage.

In 2016, sockeye returns were the worst on record—there was no distribution.

“We had our boats ready to go,” said elected Squamish Councilor Chris Lewis. “We were out there, then the Department of Fisheries closed the [waters].”

Moreover, the salmon sitting in cold storage was getting freezer-burn, so the Nation decided to try something new.

“Most people, when they get fresh sockeye, can it right away so it lasts longer, said Councillor Lewis. “For the Nation to take that extra step, a lot of people are excited.”

In August 2016, the fish went to St. Jean’s Cannery, a First Nations facility in Nanaimo, B.C. The cans were ready last fall, but weather prevented distribution until spring 2017.

“We got a lot of calls saying ‘where’s the fish, is it actually here?’” said Councillor Lewis. “People are really excited.”

Community ‘over the moon’

“I grew up having a good stock of fresh sockeye salmon every year through our food fish distribution,” recalled Adina Williams, a 21-year-old Squamish member whose family received canned salmon. “Not having that for the last few years was an emptiness in our family. It’s really nice to have sockeye back in the family.”

It is important to understand how significant salmon is to Squamish culture.

“Salmon has been a big part of my life,” said Latash Maurice Nahanee, an elder who grew up fishing on the Squamish River. “The majority went out to our aunts and uncles. My parents taught me a lot about their respect for this precious resource.”

Nahanee speaks at schools and cultural events about the importance of salmon. He often shares a legend of ancient times before the salmon came.

“There were years that people suffered and didn’t have a steady supply of food. The old people would hear their children crying at night from hunger.” According to the legend, they sought out the mythical salmon people who agreed to visit each year to provide food.

Many Squamish families still return the bones of their first salmon to the river, keeping their promise to respect and take care of this treasured, life-giving resource.

Catching the community’s fish: a challenge without Squamish fishermen

For generations, Squamish people fished along local rivers and out into the Pacific Ocean. But, as the city grew around reserve land, people chose jobs over traditional hunting, fishing and gathering.

The last time a Squamish boat caught fish for the distribution was over ten years ago.

Now, the Nation contracts A-Tlegay Fisheries Society, a group of First Nations commercial fishermen, to catch the Nation’s yearly salmon quota. However, this arrangement does not guarantee fish for the Squamish Nation.

Last year’s low returns meant First Nations commercial sockeye fishing opened for only 18 hours, according to Cheryl Martin, coordinator of the distribution. The Squamish Nation didn’t receive any fish because A-Tlegay catch for their own communities first.

A-Tlegay fishermen encourage the Squamish Nation to send out their own fishermen, according to Martin. “But there are no fishing boats. Nobody’s trained here or has those skills anymore.”

Emerging fishermen

Despite these skills waning, interest is growing among younger generations to revive old practices.

Cory Lewis was five when he learned to fish on his family’s traditional fishing grounds in the Squamish Valley, an hour drive from Vancouver.

“My uncle Dennis passed down the family legacy,” said Lewis, “not just to fish for yourself, but to fish for families and elders.”

Lewis is now in his 30s and sees it as his duty to continue the tradition.

“In Squamish, we’re blessed with all these fish. Down in Vancouver it’s hard for people,” said Lewis. “A lot of elders don’t eat fish because they don’t have access to it.”

Lewis is an ironworker, but every summer he heads for a boat.

“I love fishing. Being out on those boats catching that many fish, that would be my glory.”

While Cory Lewis dreams of bringing in a big haul for the whole community, the Nation is busy working to keep fishing traditions alive.

“We do live a dualistic kind of life where we have one foot in our traditional ways and one foot in the modern world,” said Councillor Chris Lewis.

Meanwhile, Councillor Lewis says shifting to a canned distribution was well-received—eating the same food as their ancestors is important to the community regardless of how it shows up.

“I think we’re definitely going to do it again in the future.”

Emma Loy is a Vancouver-based journalist with an interest in science and environmental issues. Follow her @emmahloy

Yusheng Cai is a journalist from China. Follow her on Twitter @yushengcai