By Sophie Gray and Anya Zoledziowski

Ed Thomas’ motorboat revs in preparation for his daily trip up the waters of Burrard Inlet into Say Nuth Khaw Yum (Indian Arm) Provincial Park, just outside of Vancouver.

For 20 years, he’s tended the Inlet’s salmon-bearing streams and rugged islands that sheltered and sustained his Tsleil-Waututh relatives, including his mother.

“Up here they could eat,” said Thomas, pointing towards the northwestern bank of the inlet where his mother grew up. “They ate the resources. The salmon, the deer, the berries, the vegetables.”

But the time he spends on his ancestral lands is more than just a pastime—Thomas has devoted his career to it.

BC Parks contracts Thomas and his four-person crew to clean campsites and report anyone who breaks park rules at Say Nuth Khaw Yum, courtesy of a hard fought co-management agreement between the provincial government and Tsleil-Waututh Nation (TWN).

That arrangement was ground breaking for First Nation collaboration with government over land use, but also exposed how many challenges remain for Indigenous communities who want control over parklands.

Setting a precedent

The agreement was sparked after the government created the provincial park on TWN traditional territory in 1995, without consulting the community.

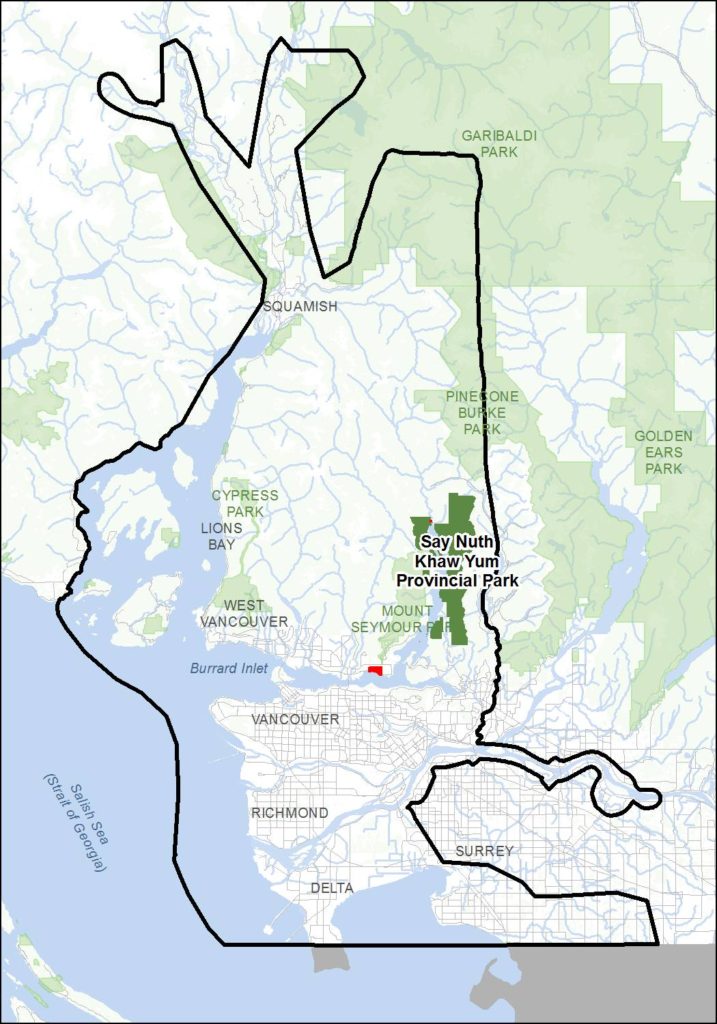

Map of Tsleil-Waututh traditional territory (outlined in black) and boundaries of Say Nuth Khaw Yum provincial park in North Vancouver, British Columbia. (Credit: Tsleil-Waututh Nation)

The First Nation demanded a decision-making role over Say Nuth Khaw Yum. Today, TWN has equal say with the province over it.

The formation of the park marked “the beginning of [the government’s] understanding of the need to be proactive in including First Nations in land use decisions.” says Vicki Haberl, the planning section head for BC Parks.

And, the call for First Nation influence over park lands has intensified across Canada since.

Last month, Federal Environment Minister Catherine McKenna voiced her support for increasing the role of Indigenous communities in protecting new parks and managing old ones.

When the government collaborates with local Indigenous communities, it’s setting a precedent for other nations across Canada, says maintenance crew member Raelene Esteban.

“Other communities should follow what Tsleil-Waututh Nation is doing,” she added.

Infographic: Timeline of Say Nuth Khaw Yum provincial park

“Our people on the ground”

While co-management highlights First Nations’ governing role over traditional lands, the work that people such as Esteban and Thomas perform is anything but glamorous.

They clean charred firewood, empty overflowing pit toilets, and remove the garbage that’s been left behind by thousands of Say Nuth Khaw Yum visitors.

The team also reports back to BC Parks whenever visitors break park rules, despite not having authority to enforce them.

“We try and report what we see, some days we report to [BC Parks] by 10 in the morning,” said Thomas. “That’s the best we can do.”

Michael George, cultural and technical advisor for TWN and member of the Say Nuth Khaw Yum governing board, said, “Putting our people on the ground to do the work that they do gives us that much more voice.”

On top of their BC Park’s contract, Thomas’ crew works to restore and rehabilitate Burrard Inlet’s ecosystem. They help clean up clam beds, increase salmon and elk populations, even rescue injured eagles.

Ongoing degradation

Despite conservation efforts, overuse of campsites and facilities has led to land degradation in and around Say Nuth Khaw Yum.

The three campgrounds overflow with visitors in the summer who regularly ignore fire bans and chop down young trees for firewood, said Thomas.

“If you go out there any weekend you’ll see smoke,” said Thomas. “You’ll see people just cutting things down for firewood.”

When the team gets to work on Mondays, Thomas says they see remnants of campfires and dead trees.

“The vegetation is now disappearing out of the little islands.”

Plus, there aren’t enough facilities to accommodate the number of visitors, with only a handful of toilets, no garbage cans, and few information boards.

“We’ve had a lacrosse team from Fort Langley come down and put down 17 bags of garbage,” said Thomas.

John Konovsky, senior advisor for TWN said, “There needs to be a reservation system so that there’s some way of controlling the number of people using these campsites.”

Too little funding

But TWN estimates it would require “a few million dollars” to curb campsite use, and a lack of funding makes it difficult to implement changes.

The First Nation devotes $10,000 per year to the co-management plan, while BC Parks contributes $15,000. According to Konovsky, these funds “don’t even pay for all the time and materials” necessary to maintain the park.

Increasing the amount of accessible areas in Say Nuth Khaw Yum is a huge priority, added Konovsky. By extending trails, park use would disperse over a wider area.

“It’s definitely a slim and trim operation,” he said. “We got $5000 from BC Parks two years ago to put up signage, that’s really about it.”

“It’s not just the job, it’s his traditional territory”

Despite the co-management plan’s constraints, Thomas loves protecting Tsleil-Waututh traditional territory.

“I don’t call it work,” said Thomas. “It’s like taking a walk in the park.”

Yet, decades of hard work have taken a toll on him. Now 65, Thomas is preparing to retire, but his crew says they’ll still turn to him for his “immeasurable” knowledge.

Shawana Michalek, another crew member, doesn’t take his retirement seriously.

“There is talk of retirement, but honestly I still see Ed coming up here. It’s not just the job, this is his traditional territory.”

Anya Zoledziowski is a multimedia journalist with a focus on race and gender issues. Follow her on Twitter @anyazoledz for a regular stream of animal gifs.

Sophie Gray is a Vancouver-based multimedia journalist with an interest in international culture and social justice. Follow her coffee addiction on Twitter @SophieGray91