By Andrew Seal and Taranjit Singh

It’s just a muddy, 52-hectare field in the middle of Seabird Island First Nation, but in a couple of months it will be lined with budding green hops as far as the eye can see.

“When we went out there and looked at the land, smelled the earth and examined some soil samples, we were speechless,” says Alex Blackwell, managing director at Fraser Valley Hop Farms.

“We immediately became convinced this was the best place for us to plant.”

The Stó:lō haven’t been widely known as tillers of soil, yet Seabird Island First Nation is embracing farming to make use of their most abundant resource: land.

“The area around the 49th parallel produces some of the best hops in the world,” says Blackwell.

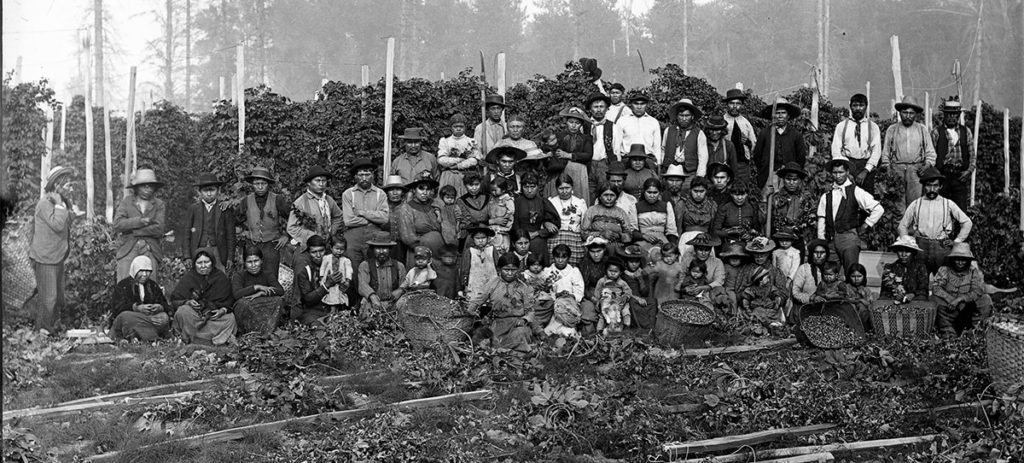

In fact, the Fraser Valley used to be the largest hop-growing area in the British Commonwealth and many Stó:lō worked as hop-pickers in the late-19th and early-20th centuries, providing them with a seasonal income between the summer and fall salmon runs.

Prohibition, tax-incentives south of the border, and the popularity of low-hop beer caused the B.C. hop industry to dwindle. In 1936 hops sold for $1.98 per pound. By 1996, the price had only increased to $2.98. But now hops is selling for $15-$20 per pound, thanks to the popularity of craft beer.

Fraser Valley Hop Farms is seeking to capitalize on these soaring hops prices, but finding a place to raise the crop in the Lower Mainland isn’t easy. That’s where Seabird Island comes in.

‘Pristine’ agricultural land

The hop farm only occupies a small portion of Seabird Island’s 700 hectares of agricultural land, most of which is leased out to local farmers by the First Nation’s development corporation, Sqéwqel. The vision statement for Sqéwqel is to work to “rebuild the traditional skill and knowledge that empower them to become fully self-sufficient and self-reliant in today’s world.”

At a time when many reserves are starting to lease land out for residential development, Seabird plans to stick to agriculture.

“We are not interested in giving up arable land for subdivisions,” says Tyrone McNeil, vice-president of Stó:lō Tribal Council and director of Sqéwqel Development Corporation.

“In our fifty-year plan, we recognize that agricultural land is going to become worth considerably more than it is today in terms of its relation to residential land.”

This has been a point of contention, though, not only at Seabird, but in many Stó:lō communities.

The Land Question

The members of Yakweakwioose First Nation, located about 30 kilometres southwest of Seabird Island, have different ideas on what to do with the 16-hectare farm that occupies about 80 per cent of their reserve.

“Some [band members] are trying to combine their acreage [of the farm] and get it developed,” says former chief Frank Malloway.

“I don’t want the whole backyard filled up with houses. A few for our own members is fine, but not plugged up the way some of the other reserves are.”

The farm has a long history. It was started in the 1940s by then chief Richard Malloway, also a former-hop-picker.

“The neighbours were all farmers and he could see that they had income all year round,” says Frank Malloway, Richard’s son. “So he said, ‘I’m going to go [dairy] farming.’”

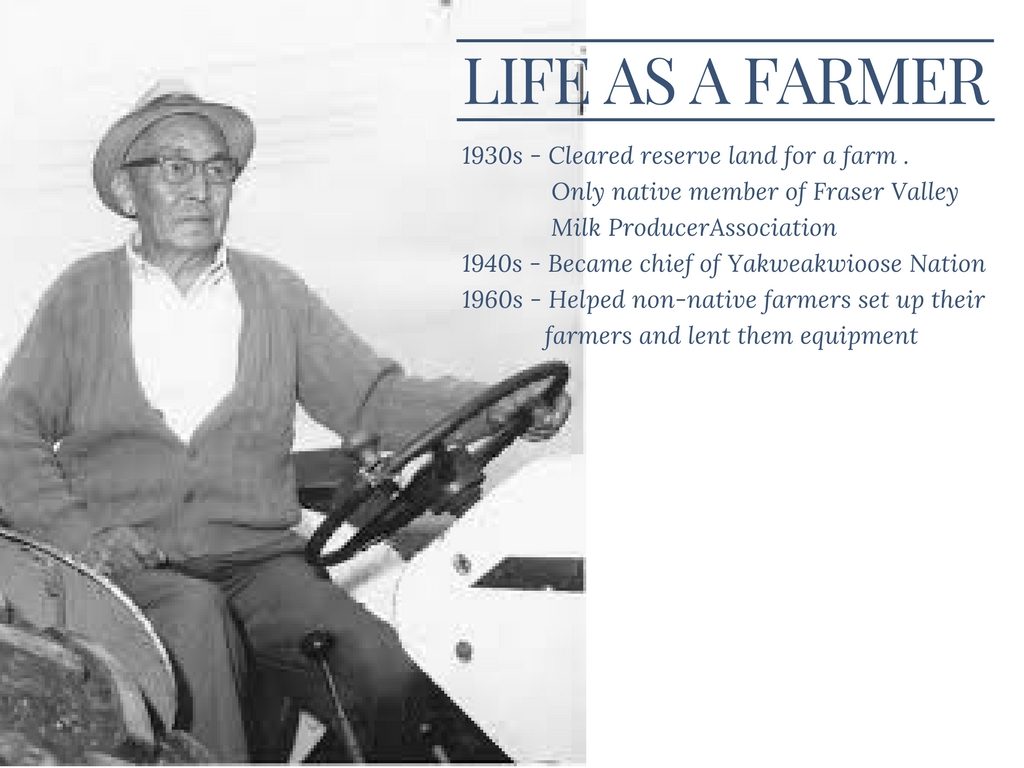

Chief Richard Malloway on his tractor at the farm in Yakweakwioose First Nation. (Elaine Malloway/University of the Fraser Valley)

Many other Stó:lō from nearby reserves, also seeking steady incomes, ventured into the dairy business around this time.

“My dad’s grandpa had a dairy farm [at Seabird Island] and was one of the biggest milk producers on this side of the Fraser. But when the province introduced the quota system, they didn’t provide any quota for our reserve so it pushed them out of dairy,” says Tyrone McNeil.

The quota system was implemented to regulate dairy supply and determine how much each farm could sell. The farmers at Seabird weren’t given any quota, and were barred from hiring lawyers to fight the province’s decision.

Richard and some of the other Indigenous farmers managed to survive the implementation of the quota, but tightening regulations continued to push them out of the market.

By the 1960s, all Fraser Valley farms were required to get a cooler for their milk. Richard was one of the few Stó:lō with enough savings to make the $2,500 purchase.

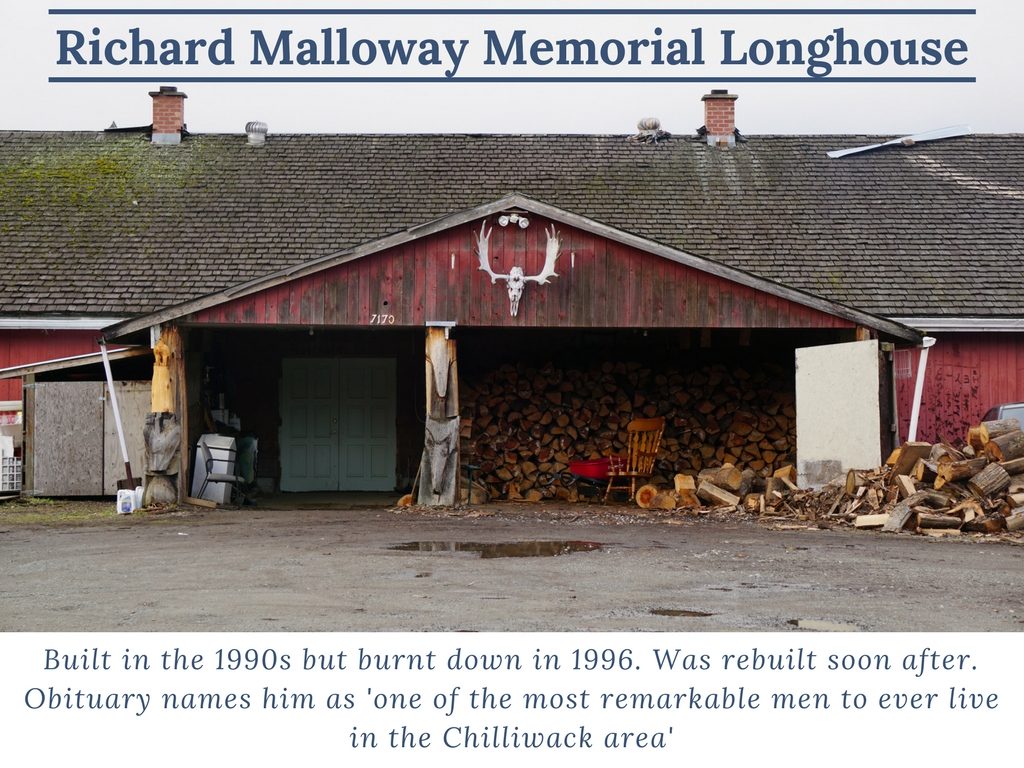

He soon became known in his community as the ‘last Stó:lō dairy farmer,” continuing until he retired in the 80s. The farm has since been leased out to non-Indigenous farmers, though its size has been reduced to make space for a longhouse and, recently, a small housing development for community members.

The Future of Farming

Leaders at Seabird Island First Nation are determined not to be pushed out of the farming business again and have set more land aside for agriculture, clearing an additional 80 hectares of shrub last year.

Fraser Valley Hop Farms are planning to expand their operation at Seabird to 140 hectares in the next two years. That could make Seabird Island the largest hop farm in Canada.

Alex Blackwell is hoping to forge strong connections to the community.

“We’re really happy to be working with Seabird, I think we’re going to build a strong relationship with them. We’re the new kids on the block but we’re looking forward to getting involved with the community and being able to offer jobs in the future.”

Andrew Seal is a Vancouver-based journalist with an interest in international issues, current affairs, and politics. Follow him on Twitter @AndyJSeal

Taran Dhillon is a Vancouver-based journalist with an interest in environment, cultures and international issues. Follow him on Twitter at @dhillonSr