By Francesca Bianco and Holly McKenzie-Sutter

Naxaxalhts’i, also known as “Sonny” McHalsie, stands precariously close to the edge of a cliff. He’s capturing an iPhone panorama to share with his Facebook friends.

This is Th’exelis. It is one of over 100 sites where Stó:lō people believe their ancestors were transformed to stone. These sites contain living spirits, or Shxweli, and stand as cautionary tales from their ancestors.

And Th’exelis’ story is one of Sonny McHalsie’s favourites to tell.

Here, the transformer Xa:ls did battle with Xéylxelamós, a medicine man who used his powers selfishly. Xa:ls transformed him into a stone in the middle of the Fraser River. The scratch marks left by Xa:ls are visible in the stone below McHalsie’s feet.

McHalsie has dedicated his career as a cultural leader and historian to collecting and sharing transformer stories – all in hopes of protecting his people’s sacred sites that are under constant threat.

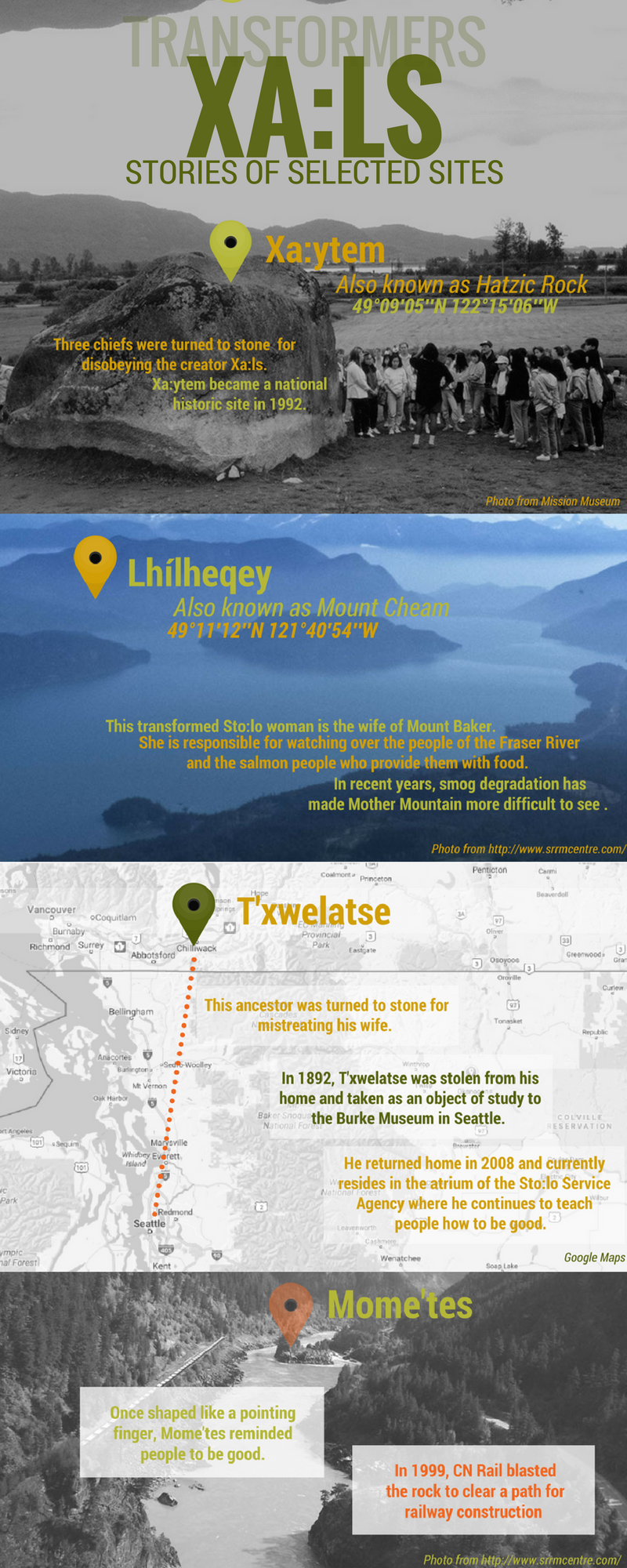

Infographic: What are transformers?

Barriers between Stó:lō people and their ancestral landmarks

Th’exelis is a breathtaking scene. But not everyone knows its history, and without a master storyteller like McHalsie to share Stó:lō’s traditional stories, these transformer sites could be lost.

In fact, some of them have been. Th’exelis itself was nearly buried during highway development. An elder from Yale First Nation had to bring in an excavator to recover the site, according to McHalsie.

Keith Thor Carlson, a professor of history at the University of Saskatchewan, has spent years studying Stó:lō culture. He thinks that in order to preserve transformer sites, there needs to be a radical change in British Columbians’ understanding of the land.

“When settler colonists come to North America, they left all their sacred sites behind,” says Carlson. “What they see is economic landscapes, then they create new myths like the frontier myth.”

Listen: Sonny McHalsie narrates the battle between Xa:ls and Xéylxelamós at Lady Franklin rock

Economic priority has cost the Stó:lō people irreplaceable landmarks. In 1999, a Stó:lō transformer site known as Mome’tes, made local headlines when it was blown up by CN Rail.

“If you’d go to France and the area surrounding Lourdes and say, ‘I am going to destroy this to make room for a Trump hotel,’ you would have people up in arms,” says Carlson.

“We need to somehow recognize the legitimacy of the human concern over sites that are regarded as spiritual human ancestors transformed in some metaphysical way beyond what a scientist can measure.”

McHalsie, for one, has made it his life’s mission to share these stories with a wider audience.

Show and tell: transformer stories shared in guided tours

McHalsie started touring the land with elders to learn their stories over thirty years ago. Those experiences turned into “Bad Rock Tours,” the name under which he offers an immersive drive through Stó:lō territory.

McHalsie spends up to nine hours on a bus telling stories and pointing out the Halq’emeylem names behind landmarks.

Recently, he led a first ever place-name tour for members of Leq’á:mel First Nation. The tour was fully booked. Preparations for their next band-specific tour in May are already underway.

Since 1985, McHalsie’s services have been booked by Stó:lō bands, school groups, and interested community members. This year, he already has more than 10 tours lined up.

But bringing the younger generation out to learn the stories of their history can pose a challenge. Schools have to contend with strict field trip regulations and low budgets within the public school system.

Rod Peters, Aboriginal Education co-ordinator at Hope’s District 78, recalls a trip that took students from Hope Secondary School to Greenwood Island, an important place name holder. The trip was guided by McHalsie.

“That field trip cost was over a thousand dollars, but well worth it for those students,” says Peters.

With a limited budget for field trips, these experiences are rare. And the transformer stories, Peters says, are seldom taught in schools.

Something old, something new

Despite challenges, new discoveries point to a hopeful future for transformer preservation.

Back at Th’exelis, McHalsie lights up when mentioning a transformer story he heard about “only just yesterday.”

Almost two years ago, Alicia Giesbrecht, a researcher at Leq’á:mel First Nation, came across a journal entry from a Nicomen Island woman. Written sometime between 1947 and 1973, the author retold the story of a woman transformed into a mountain.

When she told McHalsie about this discovery, he identified it as a transformer story about Nicomen Mountain, a landmark just a few minutes down the road from the Leq’á:mel First Nation band office.

Nicomen Mountain, the site of a newly discovered transformer story. (Alicia Giesbrecht)

Giesbrecht says she isn’t sure about next steps in this development.

“I can’t say I’ve ever discovered one before,” she says.

There are potential legal benefits to the discovery, like protecting the land from interested developers. But Giesbrecht is proud her work is playing a part in the ongoing effort to compile the lost stories of her people.

“We’re going to have that information for our members and future generations,” she says.

McHalsie is encouraged by such discoveries, saying they are “an example of communities recognizing the importance of sxwōxwiyám,” the Stó:lō origin stories.

“I find more and more today that the younger people are talking more about it,” says McHalsie. “I’m really happy people are making that connection to our land.”

Francesca Bianco is a journalist and poet from Northern B.C. Follow her on Twitter @franky_says

Holly McKenzie-Sutter is a journalist from southern Ontario with a special interest in labour and culture stories, currently based in Vancouver, B.C. Follow her @hollerdoller