By V.S. Wells and Rehmatullah Sheikh

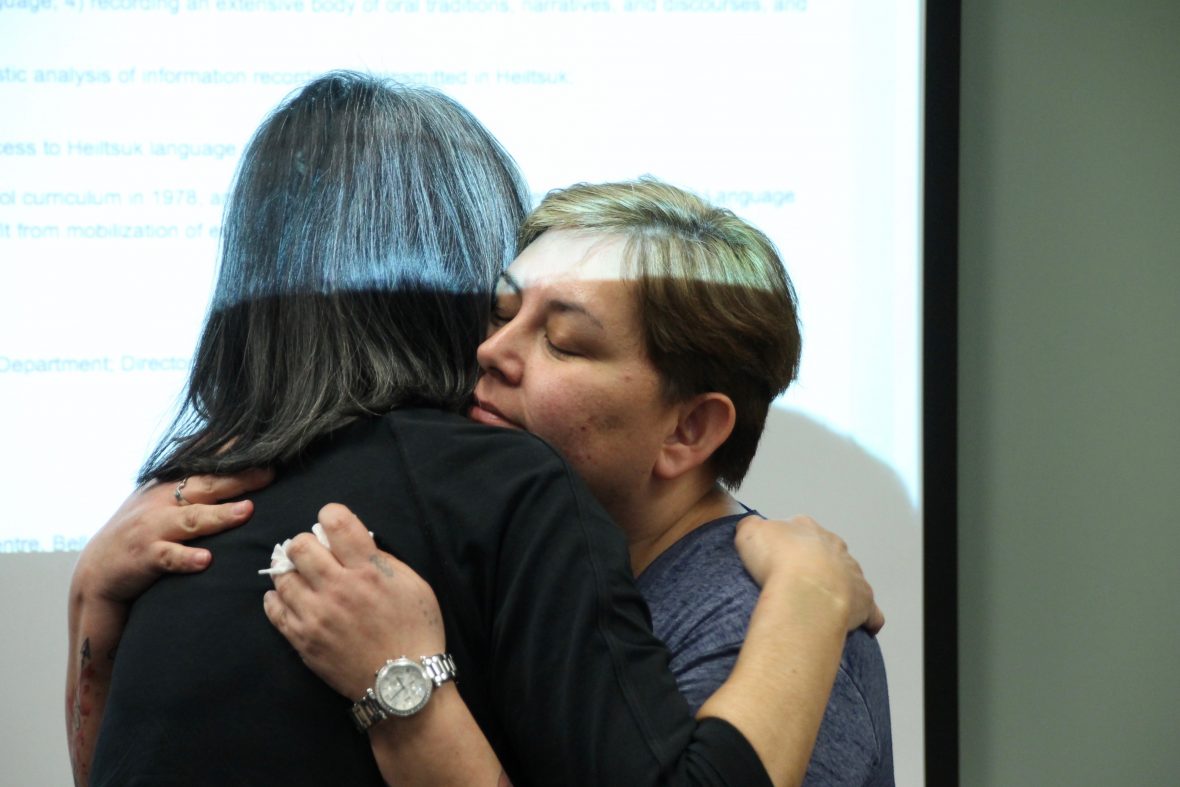

Elizabeth Wilson sat in front of a screen showing the tonal Hailhzaqvla (Heiltsuk) alphabet, surrounded by eager students from across Metro Vancouver.

Thirteen participants came to her first language class on 31 March, from elders to 11-year-olds, and Wilson was visibly emotional.

“My heart is really, really big right now. I’m so happy,” she said, blinking back tears. “All I can say is wow. Thank you guys. Wálas giáxsix̌a.”

The 11-year-old passed Wilson a box of tissues.

The classes were months in the making. Wilson had been planning this moment since moving to the city to study at the University of British Columbia in May 2017.

But starting a new language programme proved challenging. Funding and space were Wilson’s primary concerns, and the stop-gap solution — a crowded room in the Xwi7xwa Library at UBC’s Longhouse — is not feasible long-term.

Indigenous languages in cities

The B.C. government announced a $50 million-language revitalization plan earlier this year, but didn’t detail how urban language classes would be supported. 60 per cent of Indigenous people in B.C. are urban, so only funding language classes on reserves excludes much of the population.

Simon Fraser University runs Hailhzaqvla classes, but in Bella Bella, Hailhzaqv’s biggest community on the central B.C. coast, 477km north of Vancouver.

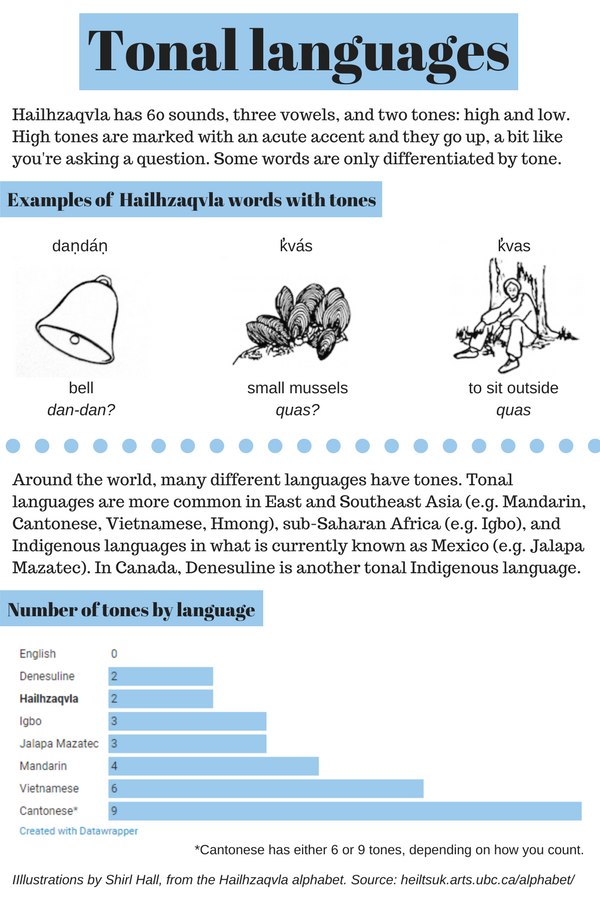

Graphic: Tonal languages

Local urban classes mean that Hailhzaqv like Wanda Christianson can finally learn her language. The 64-year-old is one of Wilson’s keenest students.

Language is part of her path towards healing from the trauma of residential school.

”At a residential school, I was only a number. This will give me an identity,” said Christianson. “And I believe that learning the Hailhzaqv language is part of my culture and part of my identity… I would like to learn my language at this stage in my healing journey to gain my rights back that were denied.”

And before the classes even began, she was excited about the idea of being in a room with fellow Hailhzaqv people, learning the language.

Wilson believes there are 50 to 80 Hailhzaqv in the Vancouver area — and the 2016 census estimates that there are less than 15 speakers in the city.

“I’ve been anxiously waiting for a language course,” said Chris Dixon, a class participant. “It is hard because we have very limited fluent speakers down here we can talk to face-to-face.”

From language trainee to trailblazer

Despite over a decade of learning, Wilson does not consider herself fluent.

She discovered her language in 2001, while working as a substitute teacher at Bella Bella Community School. She worked at the language department full-time from 2005 until 2017 and gained a teaching proficiency certificate from SFU in 2009.

The B.C. Teacher’s Commission restricted her to teaching only in Bella Bella. So enrolling in UBC’s Indigenous Teacher Education Program was her next step.

But it was an off-hand comment from her 8-year-old that made her want to teach Hailhzaqvla in Vancouver.

“Putting my son to sleep …he said, ‘I wonder how many kids that live in this city even know our language?’ And I knew the answer was … slim to none,” Wilson said. “I’m able to teach my children what I’ve learned at home. Why not teach people who are wanting to learn it that are living here in the city?”

But setting up classes hasn’t been child’s play.

Urban class challenges

Little language support exists for urban Indigenous people. The B.C. government does not include language as part of its Off-Reserve Aboriginal Action Plan, and the federal government’s Aboriginal Languages Initiative funding is designed for institutions and organizations — not individuals.

However, Wilson said people reached out to her on Facebook, proving there was interest in urban classes.

She sent a survey to potential participants and had almost 30 responses. But enthusiasm alone was not enough to set up classes.

The first class was meant to be in early February. Then, early March. One week followed another without classes.

Wilson cited space and funding as big challenges. With Hailhzaqvla learners spread across the city, a cheap central location is difficult to find.

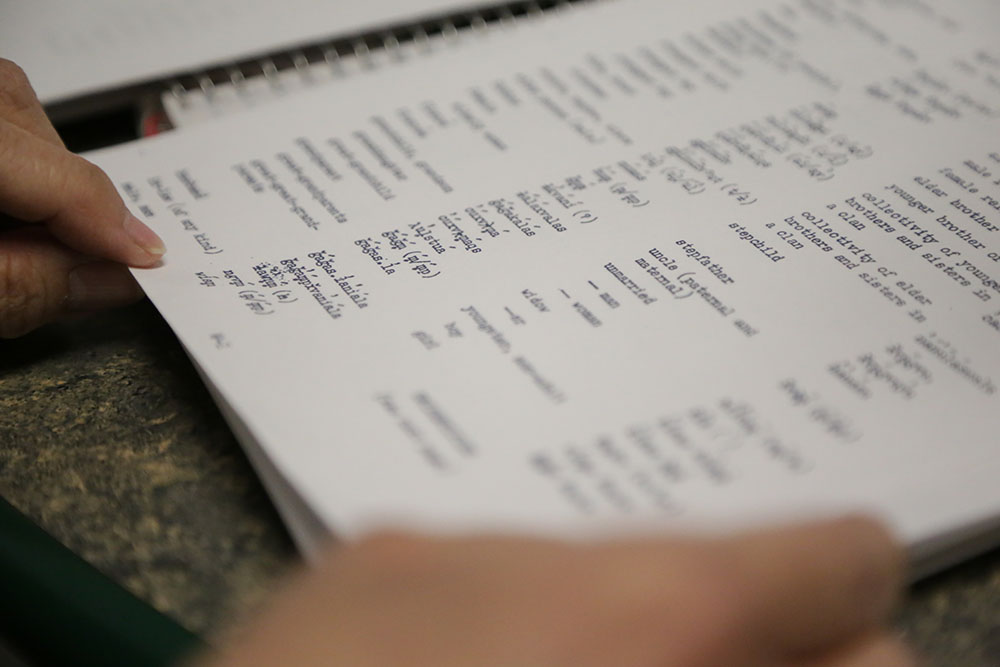

A team of UBC students, staff and faculty helped Wilson make her idea a reality — from arranging a room in the library to creating teaching tools.

“I figured maybe after the second class we’ll really figure out if the library is really the place to have it,” Wilson said. She wanted funds to cover participants’ travel costs, but could not organize that before classes began.

Ideally, the classes will move to somewhere more central. Christianson journeyed to UBC from Granview-Woodland, while Wilson lives in Coquitlam.

Wilson said she had sent a budget off to Bella Bella asking for help funding the classes, but received no response. For now, the class is volunteer-run — but it beats no class at all.

All the stresses have been worth it for Wilson.

“Our language is going to get stronger than it has, because you guys are here willing to learn,” Wilson said at the end of her first class. “And we’re going to learn all of that together. I’m really happy it’s finally here. It’s happening.”

As for Christianson, she hopes to eventually become a teacher herself.

“I would also like to… become an instructor for others who wish to learn. And I know that I can because I’m like a sponge when I learn…I delve right into it.”

About the authors

Rehmatullah Sheikh is an audio storyteller with an interest in international affairs, especially the Middle East. Follow him on Twitter: @Sheikh_Rehmat.

V. S. Wells is a Britain-born, Vancouver-based multimedia journalist. They write about social issues, technology and education. Twitter: @vsmwells