By Brenna Owen

A chorus of little voices cries out, “Éy swáyel, Mrs. Kelly!”

Grade one students in Chilliwack, B.C. are wishing their teacher, Lauralee Kelly, “Good Day” in Halq’eméylem, the Coast Salish dialect of Stó:lō communities across the Fraser Valley.

It seems a promising scene for a language classified as severely endangered.

But, as a teacher and language learner herself, Kelly faces a steep uphill battle. Chronic underfunding by provincial and federal governments has hobbled the immersion programs Stó:lō communities need in order to revitalize Halq’eméylem.

Now, there is only one actively fluent speaker.

“There’s been so much loss,” says Kelly. “We need to become fluent with our last remaining elder, who’s willing to teach it, so we don’t lose everything these ancestors left for us.”

While both the B.C. and federal governments have promised unprecedented support for Indigenous languages this year, frontline language leaders say fluency hinges on improving where and how the money flows.

‘We need to get ourselves fluent’

The loss of generations of Halq’eméylem speakers is a direct consequence of Canada’s Indian Residential School system, which included St. Mary’s school near Chilliwack.

“My Mum was one of the residential school survivors who knew the language but didn’t pass it on because of … [the] beatings she took for it,” Kelly says.

In a concerted effort to save Halq’eméylem, Stó:lō elders began working with linguists, recording hundreds of hours of storytelling and developing curriculum to train teachers.

Known as the Shxweli program, aspiring Halq’eméylem teachers connected with a handful of fluent elders for immersive learning throughout the 1990s. Kelly is one of around 20 people accredited through Shxweli.

However, none of the graduates are fully fluent, and they’re an aging cohort — teacher training fizzled after funding became sparse.

Today, there is just one Halq’eméylem teacher under the age of 30.

25-year-old Jessica Malloway kneels over flashcards she created for students at Squiala Elementary School. Soon, she will hurry to another school nearby in order to meet full-time hours.

“I do teach basic Halq’eméylem,” says Malloway. “But getting to more complex sentences, I’m starting to forget … We need to get ourselves fluent.”

‘You’re battling your own communities’

Patricia Raymond-Adair is intimately acquainted with the herculean nature of language revitalization. For almost a decade she managed the Coqualeetza Cultural Education Centre, which supports language and cultural programming in Stó:lō communities.

“We have a passion and a belief in what we’re doing,” says Raymond-Adair. “But we’re losing people, because they’re tired of the fight … I burned out too … You’re battling your own communities for the same penny.”

Coqualeetza receives annual federal funding of $132,700, which is intended to cover all of the Centre’s expenses, including wages and rent. Raymond-Adair kept cultural programs afloat by applying for short-term grants of around $15,000 from the First Peoples’ Cultural Council — the crown corporation responsible for distributing funding for Indigenous languages in B.C.

“Often [funding] isn’t available until September or October,” says Raymond-Adair, “and the money has to be spent by March 31. So, the parameters are limited and … very little gets to the grassroots, to the language teachers.”

Squiala First Nation administrator Tammy Bartz has also experienced difficulties in accessing language funding. She applied for an FPCC grant around 2005, after community members requested Halq’eméylem classes for adults.

“It took me a couple of years. I finally got a grant, which was an enormous amount of paperwork,” says Bartz.

The weekly classes only lasted around a year before the grant expired.

“It’s not enough … What nationality has to pay to learn their language?” asks Bartz.

Promise of new funding

In its 2018 budget, the B.C. government pledged $50 million for Indigenous languages. For the first time, multi-year funding is available. The FPCC is accepting proposals for grants up to $100,000 per year for three years. It could be the boost immersion programs need.

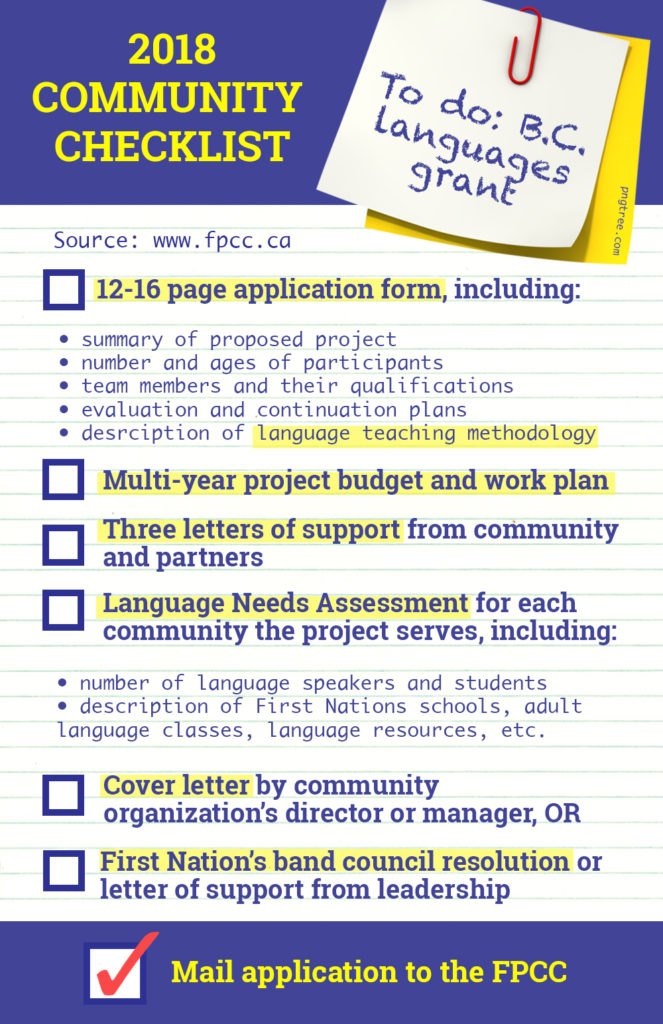

But the process to secure funding remains arduous for communities strapped for time and resources. Lengthy proposals were due less than six weeks after applications were posted.

To do: B.C. languages grant

According to Language Programs Manager Aliana Parker, the FPCC is exploring how to make the process friendlier to communities and increase existing phone and email support.

“This year, the [project-based] model will continue because that’s the infrastructure we have in place,” says Parker. “But we are looking towards … other options because we are very cognizant of the challenges that model creates for communities.”

As steady funds remain hard to come by, a handful of Stó:lō language leaders are taking fluency into their own hands.

Teachers become students

Lauralee Kelly and Jessica Malloway are planning to convene a group of teachers to learn with the last actively fluent Halq’eméylem speaker — 79-year-old Elizabeth Phillips.

“I haven’t had time to meet with [Elizabeth], but she would probably start crying,” says Kelly. “That’s her dream, to see some fluent speakers out of everything she’s done for the last 40 years.”

Kelly knows of around twelve teachers interested in joining the budding fluency group.

“If we did some kind of summer program, where all the language teachers met as if it were a job … eight-hour days, five days a week,” says Malloway, “it would be awesome.”

Because of the barriers to accessing funding, the group at Coqualeetza didn’t apply for an FPCC grant this year.

But Kelly says getting together to speak Halq’eméylem is an important step no matter what — both towards fluency and, she hopes, towards creating a Halq’eméylem immersion school, where she could teach as a fluent speaker.

“Deep down, that feeling of why I’m doing what I’m doing, it’s just been awoken up … I do have big dreams for our people.”

About the author

Brenna Owen is a community-driven journalist with a passion for solutions-focused stories across Canada. Follow her on Twitter: @brennaowen