By Jonathan Ventura and Annie Rueter

Tania Dick is a nurse in her home community of Alert Bay, B.C., where she uses the Wakashan language spoken by her family to greet patients: “Gilakas’la. Nugwa’a̱m Tania.”

“That first little ‘Hello’ in Kwak’wala just changes the whole energy and environment in the room,” said Dick, who works primarily in emergency medicine.

Across B.C., a number of health care professionals such as Dick are using Indigenous languages to connect with patients. Dick has experienced how this can create a more welcoming environment for Indigenous patients, encouraging them to return for more follow-up care.

“You can just kind of feel their guard coming down a little bit,” Dick said.

“They take a bigger breath. They are able to share what they are there for, what their needs are.”

Studies have suggested one of the key barriers for Indigenous patients accessing health care is a distrust of medical facilities.

“There is a whole generation, like my parents’ generation, that … are survivors of residential school that don’t access health care services because of their overall experiences,” Dick said.

Children at residential schools were punished for speaking their language and expressing culture, and suffered malnutrition and physical and sexual abuse. These experiences have had lasting impacts on their health.

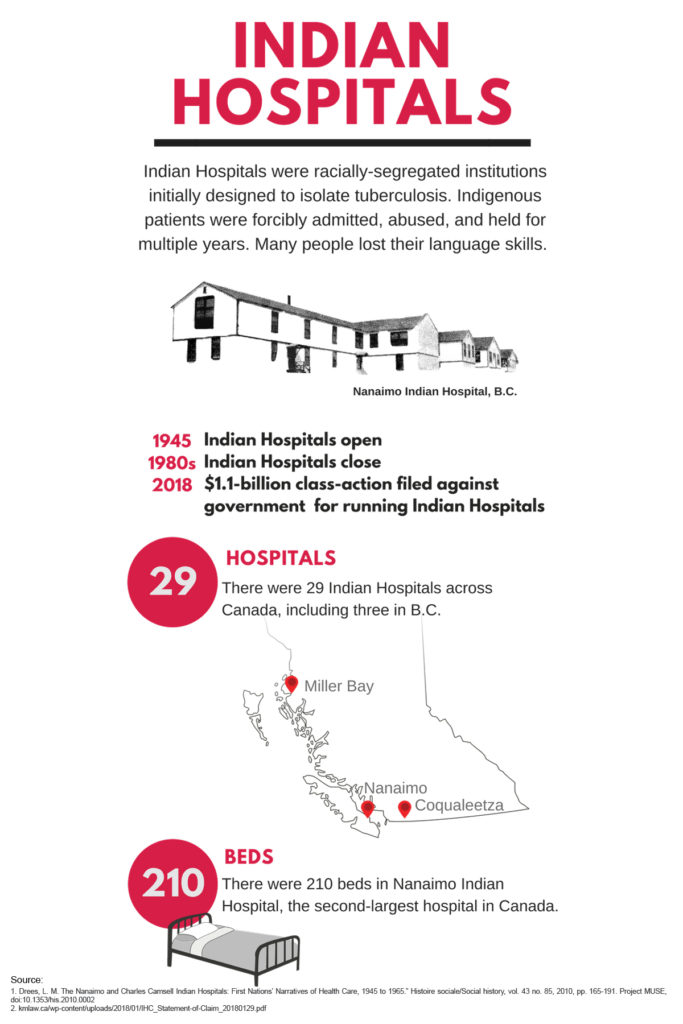

Many children at the schools also contracted tuberculosis, and Indigenous people with TB were taken from their communities to government-run sanatoriums or Indian Hospitals. Dick’s grandmother spent seven years in Nanaimo Indian Hospital, the second-largest facility of its kind in Canada.

It’s one of the reasons Dick doesn’t speak Kwak’wala fluently — she wasn’t able to learn from her family because of their institutional experiences.

Healing effect of language

Dick is among the growing number of Indigenous language learners in the province. A 2014 report by the First Peoples Cultural Council states that only 4.08 per cent of Indigenous language speakers in B.C. are fluent, but 9.3 per cent are learning.

Some studies about Indigenous health in Canada have found a connection to culture, including Indigenous languages, helps create resilience to health problems that disproportionately affect Indigenous people, like HIV, diabetes and suicide.

Roberta Price is another health care worker rekindling her relationship with language. The Cowichan and Snuneymuxw community elder works as an elder-in-residence at health care facilities in the Lower Mainland and incorporates song and language into her healing work.

The Halkomelem language has been part of her own healing journey. She spoke it fluently until age six, when she was taken into the foster care system. She now sees the impact language can have on patients – and feels it herself – when working with other elders who translate for patients from northern B.C. who do not speak English.

Price says it’s healing to witness other elders and Aboriginal patient navigators interpret Indigenous languages in hospitals. She understands how using language can make health care more accessible and create a comfortable environment.

“Part of our healing is coming back to our language, coming back to our songs, and coming to our ceremonies, and that heals a lot of people,” said Price, who shares Indigenous songs with patients.

Price is also passing down her knowledge to the future generation of doctors and nurses who are also connecting to language and culture through song and ceremony.

Identity and health

For third-year medical student Randi George, speaking phrases in Wet’suwet’en helps her connect with patients and her cultural identity. George worked as a lead medical office assistant at Central Interior Native Health in Prince George before starting medical school at the University of British Columbia.

“It wasn’t until I worked at Native Health and was dealing with kind of my own health struggles when I realized that part of my identity and cultural self is important,” George said.

“Reconnecting to my culture … allowed me to be healthier and live a more full life.”

The clinic creates a welcoming space by hanging signs in Carrier, one of the Indigenous languages spoken in the region, on waiting room walls and elsewhere in the office. Other clinics in Prince George include Carrier signage.

At University Hospital of Northern B.C., an artwork unveiled this winter includes a phrase in Carrier: “We are so happy we have a place where we can be healed. Native people can come here when we are sick, they heal us.”

Northern Health has also published a pocket-sized Gitxsan phrasebook for health care practitioners, which was well-received by Gitxsan speakers and practitioners in Hazelton, B.C. More than 1,500 copies are in print and a physician-specific version is being developed.

Language as a priority

The importance of Indigenous language and culture on health and wellness needs to be acknowledged in health care systems, according to a leader in Indigenous health.

“If our Indigenous communities are saying this is really important and this is necessary, then the health care system has to respond to that,” said Anishinaabe surgeon and medical educator Dr. Nadine Caron.

Caron sees the value language can bring in building trust and moving beyond the absence of disease to overall increased wellness. Recently, the provincial government allocated $50 million of the 2018-2019 budget to Indigenous language revitalization. There are 34 Indigenous languages in B.C.

Caron said it’s evidence language is becoming recognized as a priority. It’s certainly a priority for Dick.

“I’ll try and use that language as much as I can. Not only when I’m at work, but everywhere,” Dick said.

“It’s part of the revitalization as well. I’ve got to walk that walk and role model it as well.”

About the authors

Annie Rueter is a Vancouver-based journalist and photographer with an interest in arts and social justice. Follow her on Twitter: @annierueter1

Jonathan Ventura is a video-journalist focused on issues of accountability, justice and community building. Twitter: @jonjournalism