By Ryan Patrick Jones and Kallan Lyons

Jayden Bobb-Jollimore walks counter-clockwise around a circle formed by his fellow students, teachers, and family. The 17-year-old at Seabird Island Community School is heading toward a row of blankets elders have laid on the floor of the gym.

When he arrives, he stands on the blankets and turns toward the crowd, facing east.

He has taken his last steps as Jayden.

“Kükpi! Kükpi! Kükpi! Kükpi!” the crowd calls.

Jayden now carries a new name, a Nlaka’pamux name, as Jayden’s mother’s side is of Nlaka’pamux descent. It’s that of his late Uncle Sonny, who taught him how to hunt, fish and provide for his family. It translates to “chief.”

Bobb-Jollimore is one of 15 students who received an Indigenous name at a traditional Stó:lō naming ceremony held at the school on April 18.

The school is in an Indigenous community near Chilliwack, B.C., and it mostly serves Indigenous children. The naming ceremony is part of its effort to provide students with an Stolo-centric education and to re-introduce traditional cultural practices that were lost due to the ongoing legacy of colonialism.

“We wanted to start it because no one was getting any names handed down at that time,” said Stó:lō elder Kwosel, who goes by her Halq’eméylem name.

“We wanted to revive it.”

Kwosel was a member of the cultural committee that organized the school’s first naming ceremony in 2000. Since then, more than 200 students have received a traditional name at the school.

To reward and encourage

The ceremony connects students to their heritage and rewards performance, said Dianna Kay. She is the language program co-ordinator at the school who organizes the annual ceremony.

“How we select students is they need to be culturally aware and have demonstrated good citizenship within the school and the environment, meaning not only here but in the outside world,” said Kay.

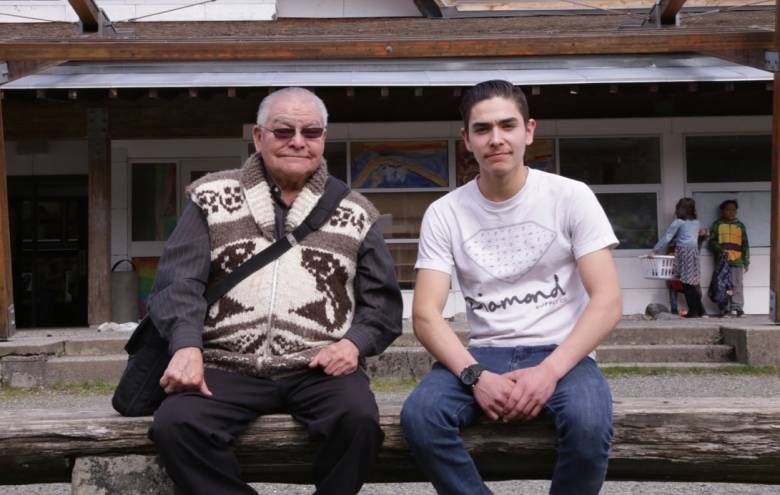

Bobb-Jollimore was chosen to participate as much for his role at home as for his behaviour at school, said Kay. Since his uncle died two years ago, he’s taken on the responsibility of caring for his grandfather, Wayne Bobb, a former chief of the Seabird Island band. He’s also shown more interest in Stó:lō culture and has become an avid hunter and fisherman.

“Before I wasn’t as much involved in my culture. I hadn’t found it yet,” he said.

“And then I started to open up my eyes and really listen and I found it. I would say I’m getting more involved.”

The school hopes receiving a traditional name will encourage students to succeed.

Makayla Sam-Greene, a Grade 12 student at the school, received the name Semiet at a ceremony when she was 10 years old. But it wasn’t until she started high school that she recognized the importance of receiving a traditional name.

“It made me want to keep working hard as I did when I was 10 years old and look forward to the future and graduate and carry myself in a really good way,” said Sam-Greene.

What’s in a name?

Historically, naming ceremonies were central to the governance of Stó:lō society, according to Sonny McHalsie, a Stó:lō cultural leader and historian. Ancestral names were passed down from one generation to the next along with rights and privileges for resource gathering. They also conveyed one’s status within the community.

“The rights and privileges would include where you could fish, where you could hunt, where you could gather berries, the stories you could tell, the songs you could sing, the carvings you could put on your house post,” said McHalsie.

But, today, the centrality of traditional names to Stó:lō society is greatly diminished. An 1884 amendment to the Indian Act that made it illegal for Indigenous people to gather for ceremonies severely disrupted the social, cultural and economic life of the Stó:lō.

How a historical ban on spirituality is still felt by Indigenous women today

“The potlatch ban didn’t allow us to have those ceremonies where we could pass things down,” said McHalsie.

“So, we lost that connection to it.”

The ban was lifted in 1951 but it wasn’t until the 1970s and 1980s that the Stó:lō began to revive naming ceremonies.

A living tradition

Today, Stó:lō naming ceremonies take place in winter at a communal longhouse while others are held in community halls, at sacred sites, or even in backyards. The school follows many of the historical protocols of community ceremonies: Guests are invited, witnesses are called, blankets or cedar are spread on the floor, and a meal is shared, among others.

But the school’s ceremony departs in some ways from tradition. For one thing, the school is responsible for organizing the ceremony, instead of the family of the person receiving the name.

“To a certain degree it kind of interferes with the families’ way of doing it,” said McHalsie.

“With [community] naming ceremonies people plan for them years and years ahead. And I think with the school it’s kind of rushed.”

Another difference is that students who do not receive an ancestral name are given a new Halq’eméylem name based on certain qualities that define them.

“I think all names should be ancestral,” McHalsie said.

“Because when you look into it that’s when you find your culture and history. That’s when you find out who who your ancestors are and who your relatives are.”

From the school’s point of view, they are giving students an opportunity to participate in a traditional practice that anchors them in their culture.

“We know that our students, they use the names,” said Kay.

“A lot of them have identity. They have place. They have being. They know that this place, Seabird Island, is a part of their home.”

Ultimately, McHalsie recognizes the importance of the ceremony to the students and believes that it contributes to the broader revival of Stó:lō culture.

“I think it’s good for revival,” said McHalsie.

“It’s just allowing the young people to know that there is a naming ceremony.”

For Bobb-Jollimore, he takes great pride in taking on his uncle’s name.

“I’d say he’d like me to carry that name on and keep it going.”

About the authors

Kallan Lyons has a penchant for long-form documentaries and reporting on social issues. Follow her on Twitter: @kallanlyons

Ryan Patrick Jones is a digital/radio reporter from the Greater Toronto Area. He is interested in international affairs, politics and urban issues. Follow him on Twitter: @helloryanjones